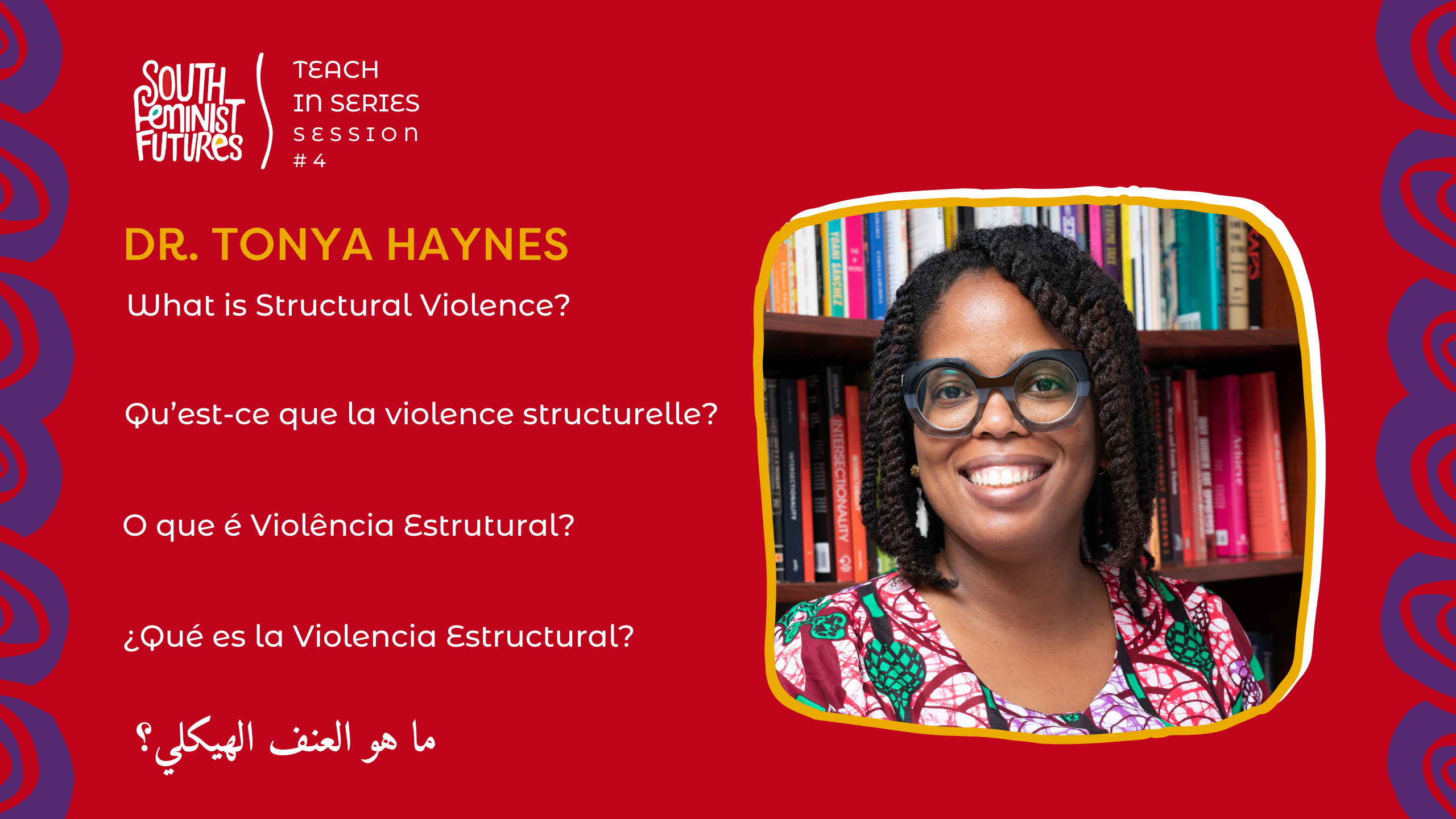

“What is Structural Violence?” is the fourth session of our Political Economy Teach-in Series. It was held on March 1, 2023, and delivered by Tonya Haynes.

Dr. Tonya Haynes is a lecturer at the Institute for Gender and Development Studies: Nita Barrow Unit (IGDS:NBU). She holds a PhD in Gender and Development Studies from the University of the West Indies and was the first graduate of the Nita Barrow Unit’s PhD programme in 2012, proudly representing a new generation of homegrown Caribbean feminist scholars.

Our South Feminist Political Economy Teach-in Series aims to strengthen intergenerational dialogue and build a cross-regional feminist constituency. The series covers various topics to interrogate and strengthen understanding of issues shaping conditions in the Global South.

Session Summary

Haynes began by explaining that structural violence is a critical way of understanding phenomena such as racism, gender inequality, climate crisis, poverty, and ableism. Specifically, the concept of structural violence can be used to analyze the inequalities between and within countries and to understand them as relations of power that are co-constitutive, mutually reinforcing, interlocking, and intersectional. Moreover, conceptualizing and applying the notion of structural stems from structural thinking. This kind of thinking:

- Helps undo neoliberal, normalized perspectives

- Allows us to examine interconnected systems and recognize that current levels of consumption are unsustainable and linked to resource extraction, as well as forced and unfree labor

- “Allows us to see the future,” quoting Tressie McMillan Cottom

In addition to McMillan Cottom, Haynes is guided in her thinking by Keguro Macharia, Paul Farmer, Johan Galtung, Sylvia Wynter, Christina Sharpe, Eudine Barriteau, Andaiye, and Dean Spade, among others.

Haynes outlined the ethical “call’ of structural violence as follows: “Structural violence calls on us to attend to the dead, the dying, the left-for-dead, marked for death, worked to death, the deselected, and the disposable.”

Structural violence occurs when preventable death happens – when life could have been saved through the deployment of available resources that are instead withheld. Haynes’ research on structural violence examines the distribution of life chances, the opportunity to live a fulfilled life, and the preventable interruption of life.

Structural violence, therefore, includes:

- The everyday violence of poverty under capitalism and stratified societies

- The “internal colonies” of people of color, Indigenous, and Black people in the US, where access to resources is unequal

- Capital city/rural divides in resource allocation

- Narratives about Haiti that frame its status as “the poorest country in the hemisphere” as something inevitable or eternal

- The “cannibalization” of dissent to neoliberalism as the only way to organize society

- Gender discrimination

- Structural adjustment policies imposed on Global South countries by banks in the Global North

- The climate crisis caused by fossil fuel and extractive industries, along with the primacy of the Western liberal bourgeois individual as the only way of being in the world

- The debt crisis, which is reinforced by the climate crisis (e.g., a small business in the Global South might rebuild after a disaster by taking on debt, only to have that rebuilding destroyed by another storm, restarting the cycle)

- The fact that 90% of people with disabilities in Barbados are unemployed

Johan Galtung, Haynes explained, defines violence as “that which increases the distance between the potential and the actual, and that which impedes the decrease of this distance.” Galtung uses tuberculosis as an example. In the 18th century, tuberculosis was considered “quite unavoidable.” But today, it is completely curable. So, if a person dies from tuberculosis despite the availability of resources, “violence is present.” Galtung shows that “violence is built into the structure and shows up as unequal power and consequently as unequal life chances.”

Comparable examples of structural violence include structural adjustment programs imposed on Global South countries that require cuts to public health services, interventions that block progressive taxation or taxes on the wealthy, and policies that produce racist outcomes. Structural violence, Haynes said, helps us “understand the absence of prevention,” such as “the lack of justice and systemic barriers to sexual and reproductive health and rights” and the prevalence of gender-based sexual and physical violence.

Importantly, Galtung notes that structural violence appears as “tranquil waters” – as the normal, day-to-day experience of life. Haynes also referenced Black feminist scholar Christina Sharpe, who describes how structural violence manifests as the weather or the climate, shaping “the totality of our environments” through forces like misogyny and racism.

Gender itself, as a compulsory binary organizing principle that “constricts,” can also be understood as a form of structural violence. For example, the imposition of the gender binary underwrites political economy. Haynes referenced Guyanese activist, writer, and theorist Andaiye, who illustrated this through her work on quantifying the amount of unwaged labor performed by women. Andaiye observed that women’s unpaid labor was central to economic policy under “conditions of low technology and weakened services/infrastructure”. As structural adjustment policies led to the privatization of healthcare and cuts to social spending, women absorbed additional unpaid work without even questioning it. In such conditions, “those who work hardest do not produce the most,” Andaiye wrote.

In response to an invitation by Haynes, attendees of the talk shared examples of structural

Violence they had experienced or were aware of, including:

- Trans and nonbinary people in Colombia being treated differently by the state during COVID-19 measures, such as enforcing specific days for women and men to leave their homes

- Black women in Brazil reporting domestic violence to the police but being criminalized or ignored

- Racialized access to food and structural violence in food distribution

- Company layoffs, particularly affecting women workers with families to support, forcing them to start over repeatedly

- State policies that prioritize support for regions deemed most productive

- The Ghanaian state using mineral resource nationalization laws to dispossess communities and enable corporate takeovers

Haynes responded to each of these examples and shared insights on effective strategies for organizing against structural violence. In particular, she emphasized that abolition movements – imagining a world without police and prisons – offer a compelling contemporary response to dismantling structural violence and shifting toward prevention. She argued that if we assume that laws alone can deliver justice, we neglect prevention efforts, asking how we might create societies where sexual violence is unthinkable rather than “the climate” or the norm.

Haynes also cited the growth of mutual aid, the expansion of care beyond traditional family structures, and activism and writing about unpaid care work as essential to revalorize, count, and recognize the contributions of women’s labor.